CJMD Quarterly Report — Winter 2026

Free speech on college campuses. An international research symposium. Research on the uses and abuses of open records — these are just some of the things we’ve been up to at the Center for Journalism, Media, and Democracy. Our quarterly newsletter highlights recent and upcoming research and events at the Center. Stay connected as we work to address some of the most important issues facing journalism, media and democracy, in both Washington state and the larger world.

Student Journalists Confront Chilling Effects, Legal Dilemmas, and Financial Pressures

The University of Washington’s Center for Journalism, Media, and Democracy (CJMD) held an event on Oct. 8th, bringing together student journalists, legal experts, and university faculty to discuss the legal rights, ethical responsibilities, and realities facing student journalists today.

The panel highlighted how student journalism is no longer just a training ground for young people who dream of becoming reporters, storytellers, and community servants. Instead, it has transformed into the front lines in the emerging struggle for freedom of expression.

From left, Matthew Powers, Mike Hiestand, Morgan Bortnick, and Piper Davidson discuss the chilling effect student journalists witness on the UW campus.

Across campuses nationwide, student journalists now find themselves covering conflicts that test not only their reporting skills but their rights as reporters. Take the recent murder of Charlie Kirk at Utah Valley University, where student reporters at the Daily Utah Chronicle had to make difficult decisions on how to cover the attack. Student journalists covering the ongoing Israel-Gaza protests have faced assaults, arrests, and even jail time for simply doing their job on campus. Censorship by institutions of higher education has also been reported. On Oct. 7 at Indiana University, administrators from the Media School instructed the student media director and student editors of the Indiana Daily Student to censor their Oct. 16 issue. When the news director pushed back against this censorship, he was terminated from his position.

The panel brought to light three main themes: the chilling effect, legal and ethical challenges such as takedown requests and financial censorship, and the expanding role of student journalists in national free speech debates.

Panelists and Their Perspectives

Morgan Bortnick, editor-in-chief of The Daily at the University of Washington, joined the paper in 2023 as a politics beat writer and now leads the newsroom, shaping its editorial vision and guiding staff through today’s media challenges.

Piper Davidson, a fourth-year UW student studying Journalism and Public Interest Communication, is a former editor-in-chief of The Daily and now reports on arts, culture, and local issues in Seattle.

Mike Hiestand, senior legal counsel at the Student Press Law Center, supports student journalists nationwide and co-led the 2013–14 “Tinker Tour USA” to promote student press rights.

Matthew Powers, UW professor in Communication and co-director of the CJMD, researches media ethics and political journalism and previously worked as a professional journalist.

“In many ways, [student-led publications] are in the crucible of some of the biggest issues regarding free speech, open inquiry, free expression in American society writ large,” Powers said.

The Chilling Effect

The biggest takeaway, according to Powers, is what journalists call the “chilling effect.” Students, faculty, and staff are increasingly afraid to speak on the record due to fear of backlash, doxing, or social isolation.

“One of the issues that student media are facing—and that both of the student panelists talked about—is that it’s become increasingly difficult to get people, students, faculty, staff, to speak on the record on these topics,” Powers said. “There is, in some sense, kind of a chilling effect that’s going on, where there’s concern for a variety of reasons, not wanting to speak or be quoted.”

This hesitancy undermines open debate and the journalistic mission to present diverse perspectives. Powers noted that social conformity plays a role in the unwillingness to speak up. While the fear is not irrational—students have been targeted for sharing their voices in university publications—the trepidation students feel about facing consequences for exercising their First Amendment rights runs counter to the foundational values of both journalism and universities.

Takedown Requests and Financial Censorship

Another key issue raised during the panel was legal dilemmas, including requests from international students to remove past opinion pieces due to safety or visa concerns. This illustrates a larger problem: when personal protection is at stake, free expression hangs in the balance.

Hiestand, the panel’s legal expert, noted that this is the first time since he began his career in 1989 that guidance for student media has been reconsidered to address such dilemmas.

Financial censorship was also discussed, in which universities quietly reduce or withdraw funding from student media to discourage critical coverage. While difficult to prove, this practice raises critical questions about press independence.

The Expanding Role of Student Journalists

Student journalists are increasingly at the forefront of national conversations about free speech and open inquiry. As protests, political conflicts, violence, and social debates unfold on campuses, university newsrooms have become the “papers of record” for some of the country’s largest and most influential institutions.

“In a campus environment like UW, there may be an observed or experienced pressure to align with dominant viewpoints or avoid controversy,” said Bortnick. “When debate is discouraged, this creates an environment of self-censorship, even if a source holds valuable or informed opinions, out of fear of judgement, backlash, and other social consequences.”

With local media shrinking, students are often the only reporters consistently covering how universities navigate these tensions. By documenting these issues with vigilance and a unique student perspective, student journalists are not only reporting on-campus news but are also shaping national dialogue on press freedom and democratic responsibility.

Looking Ahead

The primary takeaway was the importance of paying attention to these new pressures in order to support student journalists as they navigate these challenges. The CJMD plans to continue its discussions of press freedom and related issues in the future.

Connecting Knowledge and Community: KU and UW CJMD Host Inaugural Research Symposium on Technology, Democracy, and Online Participation

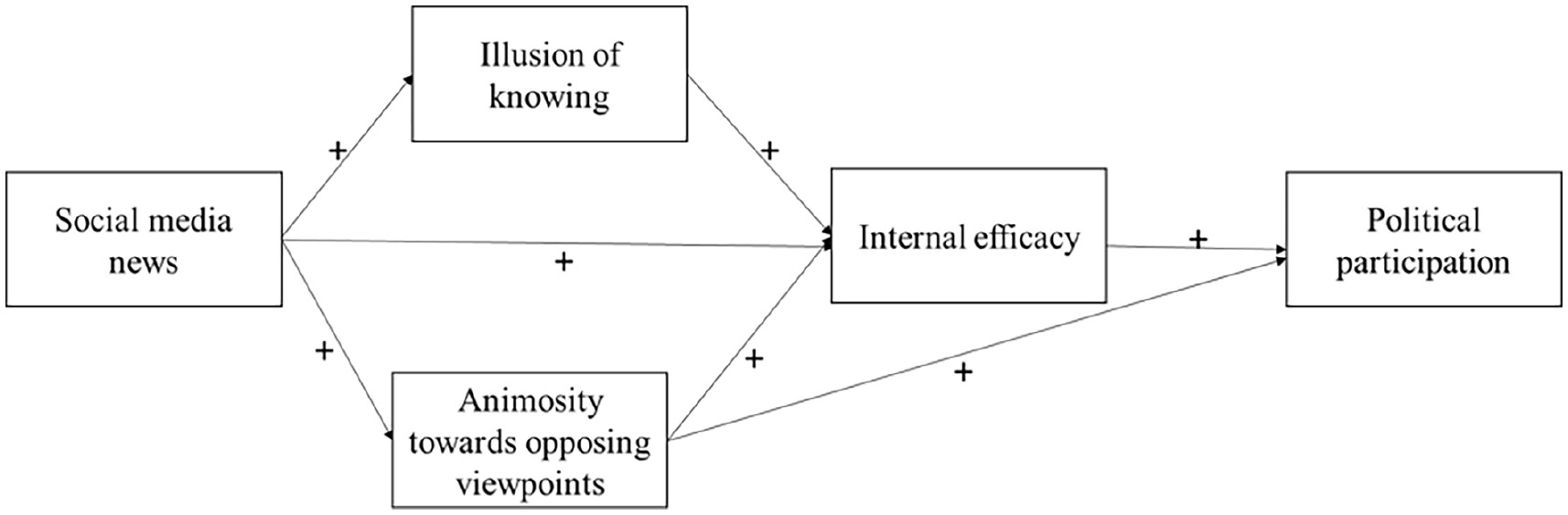

Sangwon Lee introduces his concept of the “Self-Righteous Circle,” a modified version of the Virtuous Circle that folds in the societal influence of social media on political participation.

The Center for Journalism, Media and Democracy (CJMD) hosted its first collaborative research symposium with Korea University on Nov. 19, bringing together scholars, graduate students, and faculty for a joint exploration of how people understand politics—and each other—in today’s digital spaces.

“This is really a first for us,” said CJMD Co-Director Matt Powers. “We’re both committed to the idea that few things are more important than quality journalism and creative media for society generally and democratic societies in particular.”

The event featured two research presentations that approached political communication from different angles: one examining how social media reshapes political knowledge, and the other studying what it means to feel included in online political discussions. But taken together, the talks illustrated why it is essential to study digital politics not in isolated pieces, but as a web of interacting forces shaping how we think, act, and connect.

From “Virtuous” to “Self-Righteous”? Rethinking Political Knowledge in the Social Media Age

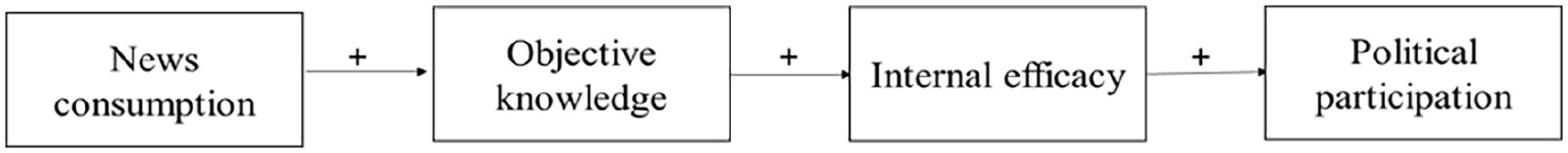

Sangwon Lee, Associate Professor in Korea University’s College of Media & Communication, opened the symposium by reexamining a long-standing assumption in political communication called the “virtuous circle”: that consuming news leads to greater political knowledge, which in turn fuels meaningful participation.

Pippa Norris’ concept of the “virtuous circle” illustrates how news consumption and political participation go hand in hand, reinforcing each other. | https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/20563051241257953

For decades, frameworks like the “virtuous circle” and the communication-mediation model have suggested that news consumption makes citizens more informed and engaged. But Lee argued that the social media environment has fundamentally altered those dynamics.

He pointed to several distinctive features of social media news consumption—selective exposure, algorithmic reinforcement, the dominance of user-generated content, constant repetition, and the blending of news with non-news—as forces that complicate and sometimes distort how people learn about politics.

Through several studies, Lee found that increased social media use often did not translate into greater political knowledge. Instead, people tended to believe they knew more than they actually did, and this inflated confidence, mixed with strong negative feelings toward political opponents, became a key driver of political participation.

In his presentation, Lee delineated the power of hate as a galvanizing force of political participation, underscoring real-world examples such as the attack on the U.S. capitol on Jan. 6, 2021. | https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2021/1/8/a-very-american-riot

He described this dynamic as a shift from a “virtuous circle” to a “self-righteous circle,” in which participation stems less from being informed and more from feeling certain and emotionally charged.

The “self-righteous circle,” dubbed so by Lee because of the emerging emotional landscape that is increasingly dominating political participation. | https://www.researchgate.net/figure/A-self-righteous-circle-model_fig2_380950469

Lee then transitioned into discussing the role of generative AI, outlining both the possibilities and risks for democratic knowledge. AI systems can make information more digestible, counter misinformation quickly, and expose people to a greater diversity of sources and perspectives.

Yet they also hallucinate, can be manipulated, and may reinforce hidden political biases, as AI trains using human data sets. And because people often see AI as neutral and authoritative, they may become less motivated to verify, question, or learn independently—what Lee called “belief in AI sufficiency.”

Lee also notably mentioned that although a media outlet and AI chatbot may report the same message, users perceive the chatbot as a more objective and trustworthy source. While note is concerning when considered with the record levels of distrust in media, it also demonstrates how AI can actually mitigate political polarization.

When it comes to exacerbating division, AI’s hands are not necessarily clean. Lee illustrated how political bias is harder to detect and regulate than gender or racial bias and remains hidden in algorithmic processes. Additionally, AI algorithms capture users’ politics and show aligned content, boosting echo chambers. And while AI can help correct misinformation, Lee warned that it can just as easily be exploited to generate persuasive falsehoods and politically manipulative content.

His final message was that technology’s impact on democracy is neither wholly beneficial nor wholly harmful, but rather nuanced and contingent on human judgement and action—the critical issue is how individuals and societies shape, govern, and use these systems.

“In short,” Lee concluded, “technology won’t decide the future of democracy—we will.”

“Do I Belong Here?” Understanding Inclusion in Online Political Discussion

Russell Hansen presented his dissertation research about feelings of inclusion and exclusion in online political discussions across platforms and different populations of people.

If Lee examined how people think they know enough to participate, Russell Hansen, a doctoral candidate in UW’s Department of Communication, explored what happens when people actually try to participate.

Hansen’s dissertation research investigates how individuals perceive their own inclusion or exclusion in online political conversations. While democratic theory emphasizes equal opportunity to participate, Hansen noted that little research examines how people feel about their place within digital political spaces, especially in environments where social cues, identities, and hierarchies are ambiguous.

To explore these questions, Hansen conducted 32 in-depth interviews with people across the United States who had participated in or observed political conversation online. The participants were purposefully equal parts male and female, and represented a broad range of ages, backgrounds, and platforms, allowing Hansen to build a nuanced account of how different users navigate political talk in digital environments.

Across the interviews, participants described the small but meaningful cues that signaled when they belonged. Some felt included when others thoughtfully responded to their ideas, asked for their perspectives, or drew them into ongoing threads.

One interviewee, a moderator on Discord, summed up this feeling clearly: “I get pulled into conversations, I can tell the people actively want to engage with me and enjoy my company and what my take on things [is]…that’s something that absolutely makes me feel included.”

Others noted that sharing something personal, and having that openness reciprocated, helped transform a simple comment thread into a space that felt social, relational, and human.

But the interviews just as often revealed experiences of exclusion. Participants described being harassed, stereotyped, “dogpiled,” or dismissed outright. Many emphasized that silence could be just as alienating and even more disliked than hostility—being ignored, blocked, or sidelined often left them feeling more unwelcome than an argumentative reply. Women frequently spoke about safety concerns tied to gender visibility, and politically inexperienced users said they felt discouraged when their contributions were brushed aside.

Ultimately, exclusion wasn’t tied to one platform feature or interaction; it emerged from mismatches between what people hoped a conversation would be and what they actually encountered.

Through thematic analysis, Hansen identified four analytic categories that shaped people’s sense of inclusion: welcomeness, recognition, safety, and a sense of shared understanding or connection. These factors didn’t operate independently. Rather, they layered together, reinforcing or undermining each other depending on the platform’s design choices, community norms, and the relational dynamics at play.

Hansen paired the interview findings with survey and experimental work, allowing him to examine how these perceptions of inclusion relate to broader political attitudes and behaviors.

Taken together, the research illustrates that feeling included is not simply a matter of being allowed to speak; it shapes how people interpret political interactions, how comfortable they feel contributing, and how they understand their own role within democratic discourse. In other words, the structure and culture of online spaces don’t just affect the quality of political debate—they influence who feels like they belong in it.

Inside CJMD’s New Public Records Study

The University of Washington’s Center for Journalism, Media, and Democracy (CJMD) has launched a new research initiative: Journalists, Transparency, and Democratic Governance. This project examines the uses and abuses of open records requests. Introduced in spring 2025 and funded by UW’s Civic Health Initiative, the study investigates whether open government laws — originally designed decades ago to bolster public oversight — still serve their democratic purpose in a dramatically changed political and information landscape.

Open records laws were created in the 1960s and 1970s with journalists in mind. Their purpose was to ensure government agencies remain accountable by granting the public access to information. But while the volume of public records requests has surged in recent years, newsrooms now make up less than five percent of requesters. This shift raises significant questions — who is using open records today, for what purposes, and what does it mean for democracy when journalists must navigate an increasingly crowded and strained system?

To answer these questions, a team of CJMD researchers—including faculty members Patricia Moy, Matthew Powers, and Adrienne Russell, two graduate student researchers Madelyn Douglas and Brooke Fischer, and one undergraduate researcher Audrey Spencer—are conducting the first detailed, localized examination of Washington State’s transparency infrastructure using the Washington State Department of Ecology as a case study. They are collecting thousands of requests submitted in 2024 and interviewing records officers, agency staff, and journalists to understand who makes requests, for what purposes, and how the use of open records laws impact journalists’ abilities to do timely reporting in the public interest

Why the Department of Ecology? A Case Study in Crowded Systems

Graduate researcher and CJMD fellow Madelyn Douglas, who helps lead the project, says the Department of Ecology offered the “perfect window” into how records requests and transparency work — and where it breaks down — inside a modern agency. Douglas explained that joining the project also offered rare mentorship opportunities: “I was really excited just to kind of get some hands-on research experience… I feel like I get, like, three times the mentorship and get to learn from each of them in really different ways.”

The department had recently updated its public records system, suggesting it might serve as a model of improved efficiency. As Douglas noted, “We looked at the Department of Ecology because they updated their public records process recently… we were hoping that because of that, they might be a model example.” But early findings show that even an updated process faces intense pressure from the volume and type of requests it receives.

On the surface, environmental agencies seem like they would attract journalists, nonprofits, or climate action and environmental justice organizations, but the research team found something different: more than half of all requests come from corporate actors, particularly environmental consultants conducting due-diligence reviews for private land transactions.

These corporate requests are not inherently negative — public records laws are designed to serve everyone — but their scale has real consequences. “Even though they’ve devoted resources to make the process smoother, there are still challenges and frictions… corporate or private interests flooding the requests, and not seeing so many journalists,” Douglas said.

These delays can stretch past 100 days — too long for reporters working under tight deadlines.

Patterns Emerging From Thousands of Requests

As Douglas’ team codes and analyzes the incoming data, several early patterns have emerged:

- Environmental consultants dominate the requester pool, often for business reasons rather than public oversight.

- Individual requesters sometimes submit high volumes of records tied to personal concerns.

- Anonymous users—hiding both their names and emails—constitute a meaningful share of submissions.

- Journalists appear only rarely, a sharp contrast to the original purpose of these laws.

These patterns raise further questions: Who benefits from the current open records system? And how can it evolve so to better achieve their original aim to enable public oversight of government action? The team is still coding data and conducting interviews, but the early insights already illustrate the gap between what transparency laws were designed to do and how they are used now.

Why This Matters Now

The Transparency Project arrives at a critical moment. Public oversight of government is crucial at all levels of government. Doing this work, though, has become harder: many newsrooms lack the resources necessary to undertake this work and request systems are burdened by growing numbers of responses. . Douglas pointed to the broader stakes: “It’s super relevant given the state of the current [Trump] administration… lack of trust and climate of misinformation make transparency and accountability more important than ever.” She also highlighted her broader research interest: “I’m really interested in the concept of transparency on a broader scale… especially looking at the narratives that big tech puts out in terms of justifying development of technology and how they’re co-opting the tech ethics space a little bit.”

CJMD’s project, grounded in local data and on-the-ground agency practices, aims to chart what is working—and where transparency breaks down—in Washington State. The ultimate goal is to help strengthen open records systems so they better support journalists, watchdog groups, and civil society actors who rely on public information to hold public and private institutions accountable.

Upcoming Events: Benjamin Wallace-Wells and Miranda Spivack

Join us on January 14 at 3:30 pm for a conversation with Benjamin Wallace-Wells, staff writer at the New Yorker.

He’ll talk about his recent article, “In The Line of Fire,” which explores the recent spate of political violence in the United States. Drawing on insights from conversations with elected officials across the political spectrum, he’ll talk about why this is happening, how elected officials are responding and what the implications are for American politics and society.

RSVP today!

Then, join us again on March 12th at 5:00 PM PST for an exciting talk with Miranda Spivack, in which she will discuss her book, Backroom Deals in Our Backyards: How Government Secrecy Harms Our Communities—and the Local Heroes Fighting Back, which was published on May 6, 2025 by The New Press. A veteran reporter and editor, Spivack’s novel underscores how corruption is most likely to be witnessed in our own communities—from local governors, mayors, town councils, school boards, police, and prosecutors. Through five U.S. case studies of “accidental activists,” individuals who questioned why those responsible for keeping communities safe, such as state and local government officials, failed to do so. In each case, ranging from car crashes and unclean drinking water to faulty safety gear, original reporting reveals the secret deals, lies, and corruption that kept the true causes of these “accidents” intentionally hidden from public view.

RSVP here!

Purchase her book here.

CJMD Student Initiative: Pushing Boundaries

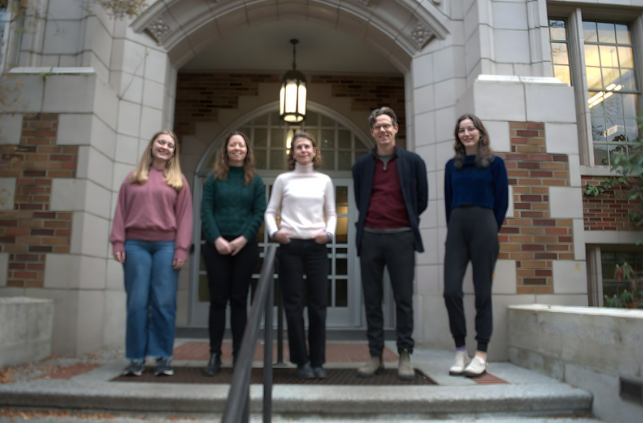

From left: CJMD Pushing Boundaries participants Elizah Rendorio, Sophia Sostrin, and Annika Hauer share ideas on how to streamline and speed-up editing processes in collaborative reporting.

CJMD launched its Pushing Boundaries initiative this fall, a program designed to support a small group of Center intern undergraduate journalists as they explore new approaches and technologies that may help address the challenges journalists face today—challenges that continue to multiply as publishing technologies evolve.

Spearheaded by John Tomasic, senior research fellow at CJMD, the program selected five students to focus on state and local collaboration, teaming with students and professionals across the country to localize national stories.

This kind of collaboration remains rare in journalism, even as digital technology has made it easier than ever. The field still largely runs on competition. National coverage increasingly dominates as state and local outlets continue to shrink. Stories are seldom developed on the ground across multiple local or state contexts and, as a result, often lack real-world complexity—making the issues they address easier to manipulate and easier to overlook.

CJMD and its academic partners worked with States Newsroom, the nation’s largest state-focused nonprofit news organization, with reporting from every state capital, to publish the project’s stories. CJMD students collaborated with reporters nationwide to examine local responses to federal food-aid cuts, changes in homelessness policy, and the rapid growth of the data-center industry.

The stories will be published in the coming weeks.

Testimonials:

Evelyn Archibald

“I initially applied to the Pushing Boundaries project because I recognized hesitance in myself while reporting outside of the capacity of The Daily. Freelancing and working without the support of a newsroom was intimidating, so I wanted to push myself in a smaller group where I would get the chance to take on more challenging stories.

“I have always wanted to work in political and national journalism, but I believe in the importance of local and public papers, so working with the States Newsroom was the perfect balance of those two spheres. I also wanted the freedom to explore more multimedia projects and stories outside of the University District, which definitely helped me build the confidence for a future reporting career in the Seattle area.

“I have always wanted to work in political and national journalism, but I believe in the importance of local and public papers, so working with the States Newsroom was the perfect balance of those two spheres. I also wanted the freedom to explore more multimedia projects and stories outside of the University District, which definitely helped me build the confidence for a future reporting career in the Seattle area.

“I’m very hopeful for the future of journalism coming out of this experience after watching my fellow students conduct themselves so professionally and passionately in their work. This generation of emerging reporters is inquisitive, driven, and with the hopeful continuation of this program, increasingly collaborative rather than competitive.

“I’ve had to ask myself some hard questions about my own reporting ethics: When can I say a story is fairly sourced? Am I confirming my bias with the questions I ask? Is my language fair and representative? Audience trust and the value my audience gets out of my work are my biggest concerns as a reporter. Especially with the story I’ve worked on with Pushing Boundaries, a look into urban data centers in Seattle, I’ve had to think about how to make lingo-heavy technology and policy reporting accessible to my readers.

“I’ve also thought a lot about how to represent data centers fully without a background in tech or engineering. I’ve learned that the most important thing is to research, ask human sources for explanations, and spend time getting it right — not just getting it done.”

Annika Hauer

“I joined Pushing Boundaries because I felt these stories would matter and challenge me in ways I don’t get otherwise — collaborating with student journalists across the nation and writing on national topics. I’ve learned how I work with others and the communication that I need. I hope those things improve in journalism.

“I liked doing these longer pieces with different localities, it feels like a reader can get out of it what is relevant to them. I think centering human stories within big topics, and reporting on solutions and issues concerning big topics through small examples (like the food pantries) was effective! It makes the story feel personal.”

Elizah Rendorio

“I joined the Pushing Boundaries project because I wanted to challenge myself to write and adapt national stories. While most of my experience focuses on local community-centered stories, I wanted to expand my abilities and try to write full ambitious enterprise stories. I hope this experience will refine my reporting skills for stories with national relevance, opening doors to more opportunities for influential reporting.

“Community-centered reporting is grounded in connection and trust with sources and readers. As a journalist, I learned the importance of immersing myself into the communities I report on, familiarizing myself with their needs, stories, and desires. There is so much to gain when you go to the places and the people you are reporting on in-person that you cannot get over the phone or through zoom. As I continue on with my career, I hope to continue challenging myself by going into the field where the stories actually happen.”

Sophia Sostrin:

“I joined the Pushing Boundaries project because I’ve always been drawn to journalism that doesn’t just report on the world around us but works actively reimagines what it could be. Coming from a background in community-focused storytelling, I felt like this project was a chance to explore different forms of journalism that can step outside the usual constraints. These could be projects that experiment, collaborate, and challenge assumed limits. The project has continued to align with what I hope journalism becomes more about: human-centered, participatory, and transparent about its process. Working on Pushing Boundaries has helped me see how innovative storytelling, community dialogue, and interdisciplinary thinking can reshape how audiences trust and interact with news.

“Collaboration can address several of journalism’s biggest challenges: declining trust, burnout, and divided audiences. When journalists collaborate across outlets, across disciplines, or even across their own lived experiences, the reporting becomes more nuanced and resilient. Collaboration distributes the emotional and intellectual labor of complex stories, reducing burnout while improving accuracy. It also mirrors the way communities actually solve problems: through shared knowledge rather than separate effort.

“Tip: Pair complementary strengths. I’ve found that collaboration works best when each contributor brings something unique; subject expertise, multimedia skills, access to a community, data fluency, etc.”