Sangwon Lee introduces his concept of the “Self-Righteous Circle,” a modified version of the “virtuous circle” that folds in the societal influence of social media on political participation.

The University of Washington’s Center for Journalism, Media and Democracy (CJMD) hosted its first collaborative research symposium with Korea University on Nov. 19, bringing together scholars, graduate students, and faculty for a joint exploration of how people understand politics—and each other—in today’s digital spaces.

“This is really a first for us,” said CJMD Co-Director Matt Powers. “We’re both committed to the idea that few things are more important than quality journalism and creative media for society generally and democratic societies in particular.”

By bringing researchers from Korea University and the University of Washington together, the symposium created a space for this kind of cross-perspective thinking, which is something both institutions hope to expand in future collaborations.

As Powers emphasized, fostering a community of scholars committed to understanding media and democracy is essential at a time when political communication is shifting rapidly. Events like this symposium help ensure that research doesn’t happen in isolation but becomes part of a broader conversation, including students, faculty, and international partners.

The event featured two research presentations that approached political communication from different angles: one examining how social media reshapes political knowledge, and the other studying what it means to feel included in online political discussions. But taken together, the talks illustrated why it is essential to study digital politics not in isolated pieces, but as a web of interacting forces shaping how we think, act, and connect.

From “Virtuous” to “Self-Righteous”? Rethinking Political Knowledge in the Social Media Age

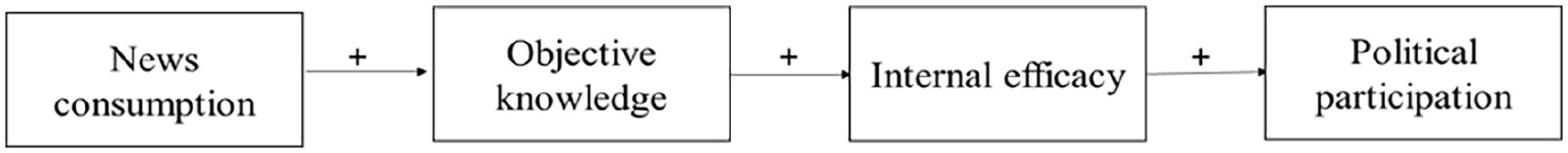

Sangwon Lee, Associate Professor in Korea University’s College of Media & Communication, opened the symposium by reexamining a long-standing assumption in political communication called the “virtuous circle”: that consuming news leads to greater political knowledge, which in turn fuels meaningful participation.

Pippa Norris’ concept of the “virtuous circle” illustrates how news consumption and political participation go hand in hand, reinforcing each other. | https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/20563051241257953

For decades, frameworks like the “virtuous circle” and the communication-mediation model have suggested that news consumption makes citizens more informed and engaged. But Lee argued that the social media environment has fundamentally altered those dynamics.

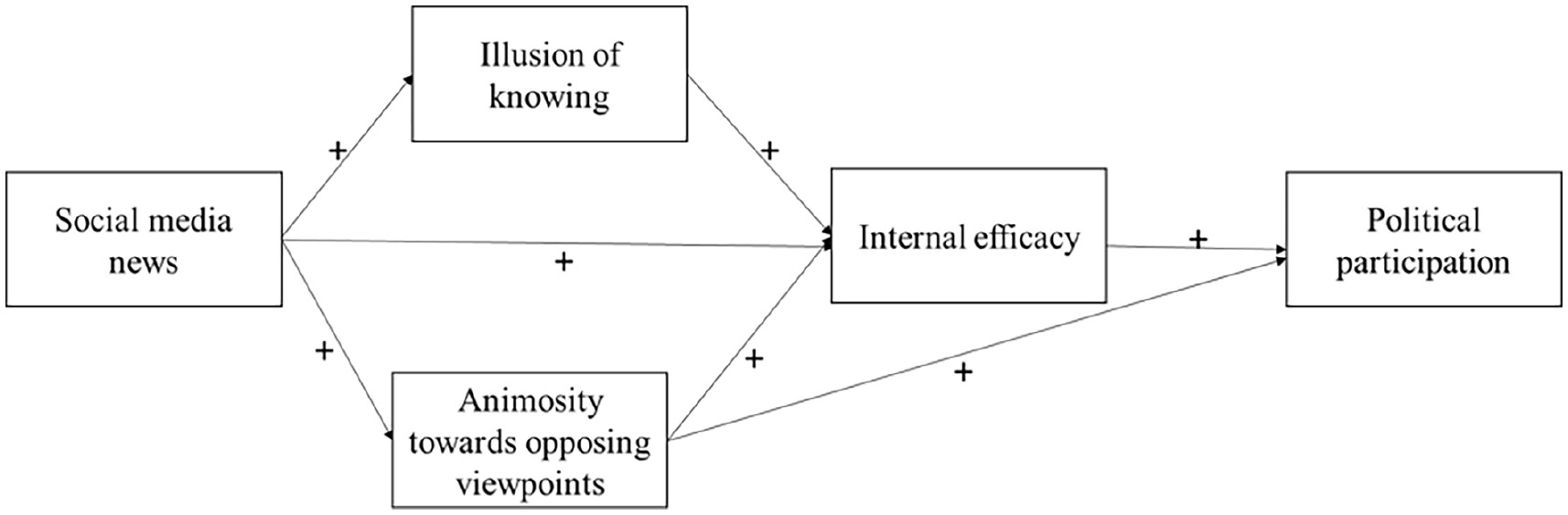

He pointed to several distinctive features of social media news consumption—selective exposure, algorithmic reinforcement, the dominance of user-generated content, constant repetition, and the blending of news with non-news—as forces that complicate and sometimes distort how people learn about politics.

Through several studies, Lee found that increased social media use often did not translate into greater political knowledge. Instead, people tended to believe they knew more than they actually did, and this inflated confidence, mixed with strong negative feelings toward political opponents, became a key driver of political participation.

In his presentation, Lee delineated the power of hate as a galvanizing force of political participation, underscoring real-world examples such as the attack on the U.S. capitol on Jan. 6, 2021. | https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2021/1/8/a-very-american-riot

In his presentation, Lee delineated the power of hate as a galvanizing force of political participation, underscoring real-world examples such as the attack on the U.S. capitol on Jan. 6, 2021. | https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2021/1/8/a-very-american-riot

He described this dynamic as a shift from a “virtuous circle” to a “self-righteous circle,” in which participation stems less from being informed and more from feeling certain and emotionally charged.

The “self-righteous circle,” dubbed so by Lee because of the emerging emotional landscape that is increasingly dominating political participation. | https://www.researchgate.net/figure/A-self-righteous-circle-model_fig2_380950469

Lee then transitioned into discussing the role of generative AI, outlining both the possibilities and risks for democratic knowledge. AI systems can make information more digestible, counter misinformation quickly, and expose people to a greater diversity of sources and perspectives.

Yet they also hallucinate, can be manipulated, and may reinforce hidden political biases, as AI trains using human data sets. And because people often see AI as neutral and authoritative, they may become less motivated to verify, question, or learn independently—what Lee called “belief in AI sufficiency.”

Lee also notably mentioned that although a media outlet and AI chatbot may report the same message, users perceive the chatbot as a more objective and trustworthy source. While note is concerning when considered with the record levels of distrust in media, it also demonstrates how AI can actually mitigate political polarization.

When it comes to exacerbating division, AI’s hands are not necessarily clean. Lee illustrated how political bias is harder to detect and regulate than gender or racial bias and remains hidden in algorithmic processes. Additionally, AI algorithms capture users’ politics and show aligned content, boosting echo chambers. And while AI can help correct misinformation, Lee warned that it can just as easily be exploited to generate persuasive falsehoods and politically manipulative content.

His final message was that technology’s impact on democracy is neither wholly beneficial nor wholly harmful, but rather nuanced and contingent on human judgement and action—the critical issue is how individuals and societies shape, govern, and use these systems.

“In short,” Lee concluded, “technology won’t decide the future of democracy—we will.”

“Do I Belong Here?” Understanding Inclusion in Online Political Discussion

Russell Hansen presented his dissertation research about feelings of inclusion and exclusion in online political discussions across platforms and different populations of people.

Russell Hansen presented his dissertation research about feelings of inclusion and exclusion in online political discussions across platforms and different populations of people.

If Lee examined how people think they know enough to participate, Russell Hansen, a doctoral candidate in UW’s Department of Communication, explored what happens when people actually try to participate.

Hansen’s dissertation research investigates how individuals perceive their own inclusion or exclusion in online political conversations. While democratic theory emphasizes equal opportunity to participate, Hansen noted that little research examines how people feel about their place within digital political spaces, especially in environments where social cues, identities, and hierarchies are ambiguous.

To explore these questions, Hansen conducted 32 in-depth interviews with people across the United States who had participated in or observed political conversation online. The participants were purposefully equal parts male and female, and represented a broad range of ages, backgrounds, and platforms, allowing Hansen to build a nuanced account of how different users navigate political talk in digital environments.

Across the interviews, participants described the small but meaningful cues that signaled when they belonged. Some felt included when others thoughtfully responded to their ideas, asked for their perspectives, or drew them into ongoing threads.

One interviewee, a moderator on Discord, summed up this feeling clearly: “I get pulled into conversations, I can tell the people actively want to engage with me and enjoy my company and what my take on things [is]…that’s something that absolutely makes me feel included.”

Others noted that sharing something personal, and having that openness reciprocated, helped transform a simple comment thread into a space that felt social, relational, and human.

But the interviews just as often revealed experiences of exclusion. Participants described being harassed, stereotyped, “dogpiled,” or dismissed outright. Many emphasized that silence could be just as alienating and even more disliked than hostility—being ignored, blocked, or sidelined often left them feeling more unwelcome than an argumentative reply. Women frequently spoke about safety concerns tied to gender visibility, and politically inexperienced users said they felt discouraged when their contributions were brushed aside.

Ultimately, exclusion wasn’t tied to one platform feature or interaction; it emerged from mismatches between what people hoped a conversation would be and what they actually encountered.

Through thematic analysis, Hansen identified four analytic categories that shaped people’s sense of inclusion: welcomeness, recognition, safety, and a sense of shared understanding or connection. These factors didn’t operate independently. Rather, they layered together, reinforcing or undermining each other depending on the platform’s design choices, community norms, and the relational dynamics at play.

Hansen paired the interview findings with survey and experimental work, allowing him to examine how these perceptions of inclusion relate to broader political attitudes and behaviors.

Taken together, the research illustrates that feeling included is not simply a matter of being allowed to speak; it shapes how people interpret political interactions, how comfortable they feel contributing, and how they understand their own role within democratic discourse. In other words, the structure and culture of online spaces don’t just affect the quality of political debate—they influence who feels like they belong in it.